Moisture‑Related Skin Breakdown: Types, Treatments, and More

Right-fit treatment for patient skin damage starts with proper identification of etiology. Listen to the full on-demand webinar to earn one contact hour.

In 2021, the Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses’ Society (WOCN®) announced approval of ICD-10-CN diagnostic codes for moisture-associated skin damage, or MASD. It validated what clinical nurses have long known: That MASD is common, complex, and costly.

Below, we’ll outline the four most prevalent forms of MASD and offer tips for identification and treatment of each. This is key to achieving desirable patient outcomes, including enhanced patient quality of life.

COMMON MASD TYPES & TREATMENTS

Moisture-related skin breakdown is caused by skin’s prolonged exposure to bodily secretions and/or effluents, often leading to irritant contact dermatitis – a nonallergic skin reaction marked by burning, swelling, itching, and discomfort. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur with or without denudation, or erosion of the skin’s surface layer[1].

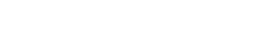

Common MASD patient risk factors include:

- Obesity

- Immobility

- Critical illness

- Diabetes

- Use of occlusive containment products (like diapers or plasticized undergarments)

- Diminished cognition

- Inability to perform personal hygiene

- Fever

- Medications

- Poor nutrition

MASD requires a structured skincare protocol designed not only to treat the suffering skin, but to decrease contact with the moisture causing it. Of course, proper treatment can only follow proper diagnosis.

Is your patient experiencing MASD? Start by examining their skin closely for symptoms (do this in high-risk patients even if symptoms don’t readily present). Turn lights on and carefully examine skin folds as well as skin beneath and near external devices. Keep eyes peeled for deviations in pigment and surface quality. These could be signs of one or more MASD types, which differ by chemical composition and moisture source.

The following four MASD types are the most common:

Incontinence Associated Dermatitis (IAD)

Prevalent and painful, IAD is caused by prolonged exposure to urine and/or fecal matter. Untreated, it can lead to skin erosion and infections from skin pathogens.

“IAD usually presents on the buttocks, perineum, gluteal clefts, and tops of thighs – areas where a patient has been sitting in, or in contact with, stool or urine,” explains Jacqueline C, Massaro, MSN, RN, ACNS-BC, CWOCN, and Certified Wound Care and staff RN nurse at Boston’s Brigham & Women’s Hospital. “Visually, IAD-affected skin is often shiny and irritated, with darkened pigmentation.”

IAD is seen in outpatient settings, where patients are handling hygiene on their own, and a variety of inpatient settings, as well. Of note: Patients experiencing IAD are at especially high risk of developing pressure injuries.

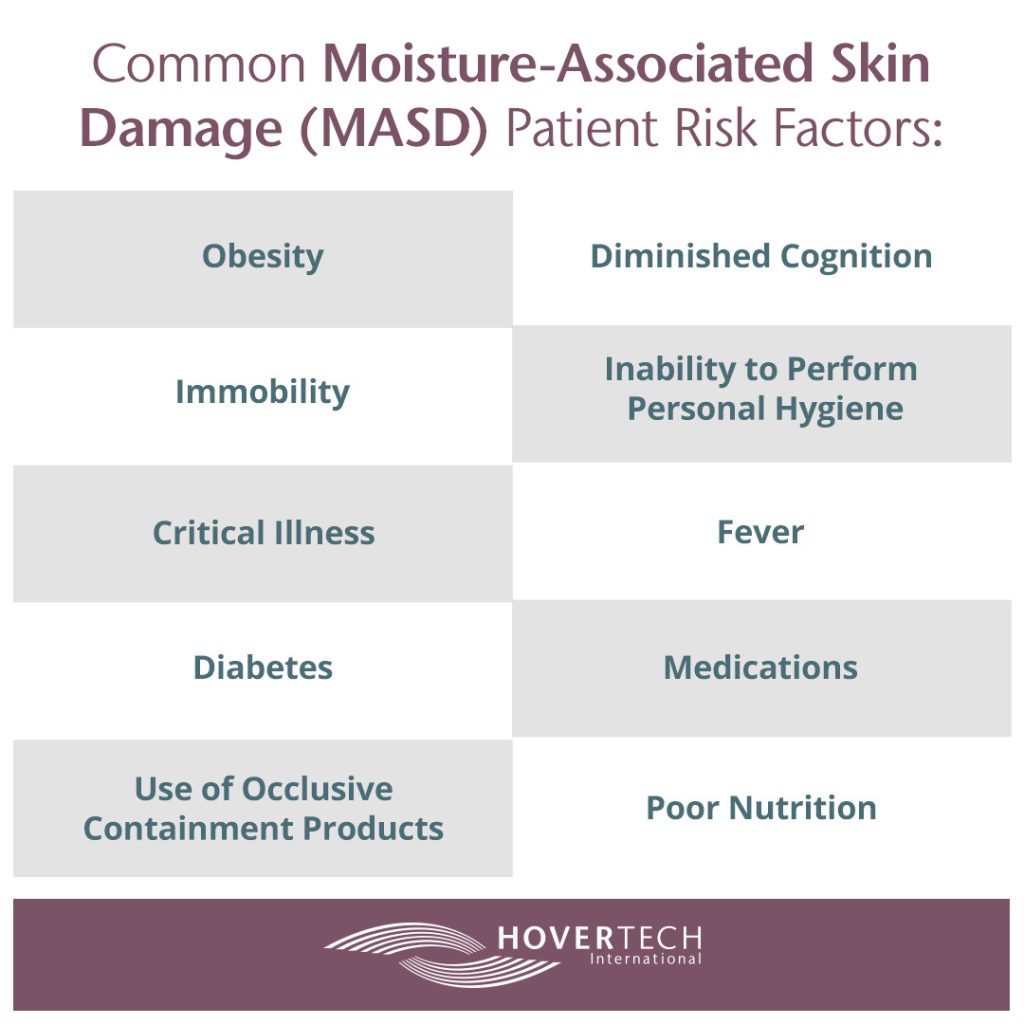

Treatment of Incontinence Associated Dermatitis

IAD is best treated with a pH balanced skin cleanser that mimics skin’s natural acidity, as well as with skin barriers (liquid barrier films or ointment). A few more notes on treating IAD:

- Avoid diapers or chux. Use absorbent underpads and/or briefs that wick away fluids.

- Avoid cleansers containing harsh chemicals or fragrances.

- Not every IAD case has a fungal component. Still, many patients and caregivers reach for anti-fungal treatment. If a secondary fungal component is present, treat it for the amount of time ordered by the licensed practitioner, then return to non-fungal treatment.

- Contain or divert incontinent urine or stool. Many devices on the market can help with this. Choose one that’s a fit for the patient’s size, gender, and circumstances.

- Consider a therapeutic support surface, such as a low air loss mattress or bed, that can help with the microclimate and management of moisture and evaporation.

- Encourage patients to wear nonrestrictive, absorbent clothing and to avoid wool and synthetic fiber whenever possible.

Intertriginous Dermatitis (ITD)

ITD develops on skin in contact with other skin, such as the axillae, neck creases, intergluteal and intra-abdominal folds, under breasts, and in between toes.

In ITD, the moisture source is perspiration that becomes trapped either within the skinfold or beneath occlusive clothing or footwear that doesn’t allow evaporation of sweat. The severity of inflammation and highest likelihood of denuded skin are found at the deepest portion of the skinfold, where friction and chronic moisture are greatest. For this reason, ITD often isn’t seen until and unless you lift a skin fold and look inside.

Patients with ITD are also at risk of secondary cutaneous infections due to the warm microclimate. Fungal infections are often common and are usually marked by spotty satellite sores.

Treatment of Intertriginous Dermatitis

IAD treatment guidelines above apply to ITD, with a few additions:

- When applying cleansers to IAD, avoid scrubbing. This creates friction that can worsen skin breakdown. Use soft cloths and clean gently. Fabric impregnated with silver can help keep bacterial load down and provides stellar wicking.

- Avoid talc and cornstarch, which cake and merely absorb, ie. don’t treat the problem.

- If satellite lesions exist, treat those with anti-fungal treatment. Switch to a regular barrier treatment after the fungus resolves.

- Consider use of absorbent pads or non-occlusive, high-airflow incontinence pads.

Peristomal Dermatitis

Peristomal dermatitis results from prolonged exposure to drainage from a digestive stoma or fistula (both of which require pouches), be it urine, stool, saliva, or digestive secretions. External exposure to moisture, from bathing or swimming, may also contribute to development of peristomal MASD.

“Often peristomal dermatitis starts when moisture from eroded skin causes the seal of a pouch to detach from said skin, allowing contact with the stoma effluent, further damaging skin,” explains Diane Bryant, MS, RN, and CWOCN who practices as a Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Clinical Nurse Specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The affected skin area typically begins at the stoma or skin junction and extends outward, following the flow of effluent. Borders are usually indistinct. Peristomal dermatitis is more common in outpatient settings, pointing to the importance of educating patients on how to maintain pouch seals at home.

Treatment of Peristomal Dermatitis

Carefully and comprehensively assess at-risk patients, and not just in lying position. Sit them up to see whether changes have occurred in the stoma and/or in contours around it. If a patient is complaining of discomfort or leaking, remove the skin barrier and check for erosion. A few more notes:

- Assess the stoma and determine the size of the skin barrier and need for convexity. Be sure to match skin barriers to body habitus. This usually involves cutting barriers to an eighth or sixteenth of an inch, which often requires convexity. Luckily, there’s a variety of convex products on the market.

- Treat peristomal skin with a dusting of pectin-based powder sealed with a non-alcohol liquid skin barrier spray.

- Also consider skin barrier pastes, strips, rings/seals, liquid sealants powders, and belts. Belts are especially affordable and effective.

- Educate patients and caregivers on signs, symptoms, and prevention. Stress the need for periodic remeasurement and adjustments to pouching systems and tubes and lines.

- Some patients extend products for too long due to financial constraints. Explore whether a patient might have financial concerns related to supplies, and, if so, work to identify available resources.

- Encourage use of a cool hair dryer to help dry skin with less friction following bathing or swimming.

- Remind patients that they might need to change skin barriers more frequently in humid climates.

Periwound Maceration

Periwound maceration occurs when wound exudate, proteolyse enzymes, and cellular debris have prolonged contact with skin within four centimeters of the edge of the wound. Chronic wounds are a heightened risk, as they contain more enzymes than acute wounds and are often more exudative. Macerated periwound tissue is soggy, soft, and abnormally white or gray and wrinkled.

Treatment of Periwound Maceration

Overhydrated skin takes longer to heal and is at heightened risk for infection. Don’t assume that a highly-absorbent dressing and more frequent dressing changes are enough. Take the extra step: protect the periwound area with a liquid film barrier. A few more tips:

- Moisturizers and/or skin sealants can be applied preventatively to skin surrounding the wound to prevent development of dermatitis.

- Allow a liquid film barrier to dry before adding dressing. Many newer products can be directly painted onto the skin.

- Get the wound history. Wounds are, after all, often a window to a patient’s larger health.

- Educate patients and caregivers on changing dressings frequently and noting any changes. In heart failure patients, for example, increased wound draining can indicate the need for a diuretic tweak.

For a more in-depth talk on moisture-related skin breakdown treatment and to earn one free contact hour, listen to the full on-demand webinar.

[1] https://www.google.com/search?q=what+is+denuded+skin