Laparoscopic Cholecystectomies: Pre‑Operative Considerations for New Nurses

Earn one contact hour. Listen to the full, free webinar on pre-operative considerations for laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

This seemingly routine surgical procedure is actually quite complex. Listen to our full webinar recording on the topic to earn one contact hour.

Read on for detailed helpful guidelines.

Cholecystectomies are common in the United States. More than 1.2 million patients have their gallbladders surgically removed annually[1]. In 2019, the procedure was the third most frequently-performed ambulatory surgery.

While common and minimally invasive[2], though, laparoscopic cholecystectomies are nonetheless complex, presenting learning curves for newer nurses in particular. Most perioperative nurses begin their careers in general operating rooms and are likely to encounter this procedure. A clear understanding of laparoscopic cholecystectomy protocol and best practices is therefore critical. Below, we’ll outline tips for a whole-patient approach to laparoscopic cholecystectomy that can help nurses adequately prepare, increasing the likelihood of positive patient outcomes.

Gallbladder Disease Recap

Gallbladder disease is a blanket term for inflammation, infection, stones, or blockage of the gallbladder – the muscular sac beneath the liver that stores 50% of the liver’s bile. Gallbladder disease affects 6 million men and 14 million women in the United States, with higher rates among Native and Hispanic Americans. Cholelithiasis (the formation of gallstones, sometimes called gallstone disease), cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder itself), and choledocholithiasis (gallstones that have passed into the common bile duct) are gallbladder disease’s three most common causes.

Until the early 1990s, all cholecystectomies involved an open procedure in which the gallbladder was removed through an 8- to 12-centimeter incision below the right rib cage. In decades since, laparoscopic cholecystectomies (and more recently, robotic cholecystectomies) have become the norm[3]. Through several incisions measuring no more than 2.5 centimeters each, surgical instruments and cameras are inserted into the abdominal cavity. After the cystic duct and cystic artery are identified and dissected, the gallbladder is removed through one of the ports[4]. Today, 92 percent of cholecystectomies are performed laparoscopically[5], offering better quality-of-life outcomes than the open surgery alternative[6]. Still, there are risks – chief among them, bile duct injuries, bile leaks, bleeding, and bowel injuries. In adults ages 65 and older, laparoscopic cholecystectomies may be associated with higher morbidity and mortality with acute gallbladder disease.

Control the Factors You Can

Arguably more so than other common surgeries, laparoscopic cholecystectomies benefit from nurses who exercise thorough pre-operative preparedness. This begins by gathering a clear understanding of the patient:

Why is the patient undergoing a cholecystectomy? What’s the diagnosis? What symptoms brought them here? Discovering that a patient has had previous abdominal surgeries, for example, allows a nurse more adequately prepare for the unexpected, like a possible switch to an open cholecystectomy.

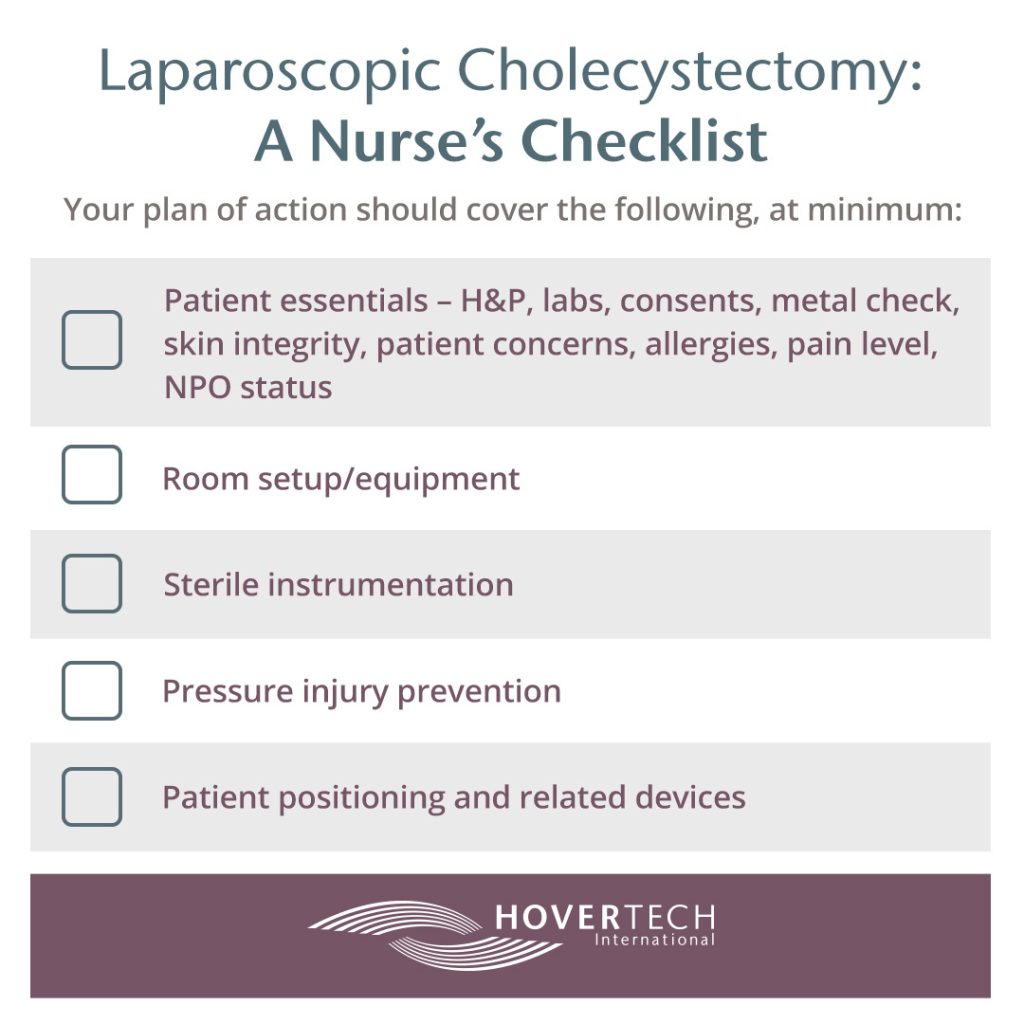

The following list covers the minimum pre-operative considerations every nurse should cover while preparing for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Whenever possible, communicate specific questions to the patient instead of relying solely on their chart:

History and physical examination (H&P)

Has the patient recently undergone other procedures (for example, an ERCP – endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography – which commonly precedes cholecystectomies)?

Labs

Has the patient had elevated bilirubin levels? Lipase levels? Have they undergone type and screen or type and cross?

Metal

Does the patient have metal on or inside their body? Where? Remember that older tattoos can be metal-bearing.

Skin integrity

Are there signs of pressure injuries, such as purple-ish or discolored areas, or patches of skin that feel warm, spongy, or hard? Failure to accurately capture this information can put the operating room team at risk if skin integrity declines in the near future.

Patient concerns

Has the patient expressed any specific worries or anxieties?

Allergies

Is there a history of allergies? To what?

Pain

What is the patient’s pain level? Could pain be causing issues mistaken as symptoms, such as nausea?

NPO (nothing by mouth) status

Double-check verbally whenever possible.

With these essentials inventoried, begin formulating a plan of action. Here are some essentials to consider before the patient enters the operating room, in no particular order:

Room setup/equipment

Review the surgeon pick list. This should cover, but is not limited to, patient positioning, skin prep, medications, equipment, surgical instruments, and supplies. Do you feel comfortable with the instruments? Have you used them before? If the need presents for a switch to an open procedure, who is responsible for gathering necessary equipment? Will the argon beam be necessary if the patient’s liver is especially friable?

Sterile instrumentation

A circulating nurse collaborates with scrub person to supply the necessary items. Communication is key to ensure everything potentially needed is on deck.

Pressure injury prevention

Is padding needed for bony areas, sacrum, or heels? Remember, procedures lasting more than 3 hours put patients at higher risk of surgery-related pressure injuries. Deep pressure injury can take up to 72 hours to present at skin level. Talk to wound care specialists and nurses: What can be done to alleviate injuries you might not even see?

Patient position and related devices

Make sure patient’s head is in neutral, eyes are protected, and more – keep reading.

Common Oversights: Patient Positioning and Pressure Injury Prevention

Proper patient positioning sometimes gets lost in the OR shuffle, but it is essential to whole-patient thinking. After all, for several hours the patient will be lying unconscious. Positioning is inextricably tied to critical factors like hemodynamic stability, oxygenation, and protecting the IV site.

Positioning specifics are impacted by many factors including nutritional status and body mass. Tools and devices to help achieve correct positioning include pink pads, arm boards, gel donuts, and pillows for under knees. A device particularly well-suited for laparoscopic cholecystectomies is the HoverMatt® T-Burg™ (Trendelenburg Patient Stabilization & Air Transfer Mattress). The HoverMatt® T-Burg™ attaches to the operating room table in less than sixty seconds and prevents unwanted patient movement in steep Trendelenburg. With air-assist technology it is designed to address a number of patient issues including safe transfer from the OR table to PACU. The breathable HoldFast™ fabric supports a microclimate that contributes to skin integrity, meaning it can remain under the patient for the entirety of their stay. This is especially critical when considering the fact that hospital acquired pressure injuries (HAPI) affect as many as 2.5 million patients each year – and are the financial responsibility of the hospital or systems caring for patients at the time the sores present.

Did you find this blog helpful? Send it to a fellow RN. Learn more about laparoscopic cholecystectomy preparation and earn one contact hour listening to a webinar by Shosha M. Beal MSN, BSN, RN, CNOR.

Want to learn more about the HoverMatt® T-Burg™ and other patient handling and positioning tools? Contact HoverTech International.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448176/

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448145/

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448145/

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cholecystectomy#Laparoscopic_cholecystectomy

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448176/

[6] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10653229/#:~:text=Conclusions%3A%20Laparoscopic%20surgery%20has%20demonstrably,%2C%20splenectomy%2C%20and%20esophageal%20surgery.